|

By contrasting nationalism with imperialism it becomes clear why the first is so much more preferable, says Yoram Hazony in a recent book

As we are bracing ourselves for the finale of Britain’s Brexit move, there is a plethora of opinions and articles telling us why this is a reckless move, yet there are very few cogent arguments as to why exiting the European Union (EU) makes total and logical sense. The Israeli writer and academic Yoram Hazony does not make the Brexit case per se, but he sets out a compelling argument that explains the evil that has befallen mankind from empires that have subdued nationalism in favour of all encompassing dogmatic visions of a better future. One does not have to look very far – Hitler, Stalin – to find some real life evidence and Hazony makes it clear that none of these men espoused nationalist instincts, in fact they sought to destroy these and therefore any comparison of present day nationalist tendencies are nowhere close to fascism or Nazism. Hazony explains the continuum of the tribe that amalgamates with other tribes, in turn to form a nation, which in a possible next step could become subordinated by a larger empire. And while some may think it is rich to compare the former Soviet Union to the European Union, the dynamics are similar: a dominant nation leads the formation of a union, gives it an ideological foundation that is mostly unquestionable and the resulting combination will lead us to some sort of nirvana where the sovereignty of all constituent parts has been eroded, because in a perfect world you do not really need it. And where the Soviet Union was driven by Russia, in the new world Germany is more or less the force of empire: that which it was not able to do by force, it now has accomplished through ‘peaceful means’. I would add that the EU is not primarily driven by Germany; there is a Franco-German axis that has been moving this process forward. In that process in particular Belgium and Luxembourg act as the willing henchmen (think Juncker and Verhofstadt) executing the project and dragging along the naysayers. The essence of the book is in how we need to understand ‘nationalism’ in positive terms as something that has helped build great nations and Hazony keeps going back to the examples of the British, French and Dutch ventures as they emerged and enabled phenomenal social, economic and cultural growth. He is right and it is also why we are seeing strong anti-EU movements in each of these very countries. As a born Dutchman, I fully subscribe to his positions, as the blood and toil of the 80-year war (1568-1648) that created its independence and unique culture (the consensus model that aligned Protestants and Catholics) has been signed away without much of a proper public consultation or vote. In the 1980s and 1990s we were taught and we all believed that ‘Europe’ was a good thing, a wealth and peace creator and no one in his or her right mind should question it. We consequently did not. My arrival in Britain 1990 however provided me with a crash course in the downside of the European project, poignantly summarized by one of my erstwhile British colleagues who asked me “When did the European Economic Union as it was always known become the European Union?” I had no answer, it just happened. Now that I am based in Canada and travel back to Europe regularly it has been bewildering for instance to see military on the streets of Athens to enforce the country’s debt restructuring. It has essentially turned Greece into some sort of indentured servant owned by the EU, mostly as it turns out by Germany. The omnipresent EU flag is now flown alongside the national flags and the question is when will it replace native colours entirely? At least the Dutch have recently decided to display their ‘red-white-blue’ in parliament to at least have a sense of national identity in the top-down avalanche of Euro-blue. Here in Canada I often wonder how all the liberals who speak so approvingly of the European project would settle in a world where their capital was in Dallas instead of Ottawa, their currency was the Americano and where, despite all well intentioned assurances, an American elite would drive most if not all of the decision making? The point Hazony makes of course is that the more authority you let go and delegate upwards, the likelier it is you will never get it back. In the process national identities and decision making erode and at the local tribal level the average citizen will have a hard time to identify with the group and leadership that now apparently has come to represent them. The Brits consequently have taken an entirely logical step to try and release them from the imperial EU project. Maybe they can provide a way, much like Thatcher laid out, where independent European nations live and work together without such crushing tools as one currency or one political center. An eight percent blow to British GDP may in the end be a small price to pay for freedom and avoid the demise of their nation. The book lays out a clear argument, but in the final chapters Hazony takes his reasoning one step further by explaining how this love of empire leads inevitably to deep criticism (and eventually hate) for countries that cling to and fight for their national identity and freedom. The USA, Hungary and Poland are getting the steady stream of abuse as we all know, but in no other case is this meted out as regularly and as harshly as against Israel. The Jewish nation has been so successful for close to 4,000 years precisely because it never sought empire, as instructed in the bible where good neighbourly relations where laid out as a guiding principle. Jews also learned that no nation would lift a finger to prevent their annihilation, their justifiable claim to security has forever been shaped by that one experience, the Holocaust. The contempt for Israel is – apart from the reflexive and deep rooted anti-Semitism – driven by looking down on the Jews’ outdated attachment to the concept of nation in a world where open borders and joint sovereignty is the way forward, according to the ‘European elites’. Hazony puts it succinctly when he argues that Auschwitz helped create Israel, but Israel’s critics argue that Jews by standing up for their nation’s borders and freedom have essentially become Auschwitz. Think that one through. Hazony’s book is a thought provoking and refreshing read. So it is sobering to see how far the European empire has moved ahead and how deep the hate is against those nations that are swimming against the tide. Yet it may not be too late, but unwinding the EU will be an unpleasant and potentially violent (Brexit, the riots in Paris) process. Letting it go forward unchecked however will not be unpleasant, it will be dark. Photo: the EU blue alongside the Bulgarian flag in Sofia, June 2018.

1 Comment

Some lessons for life and political success: staying at it

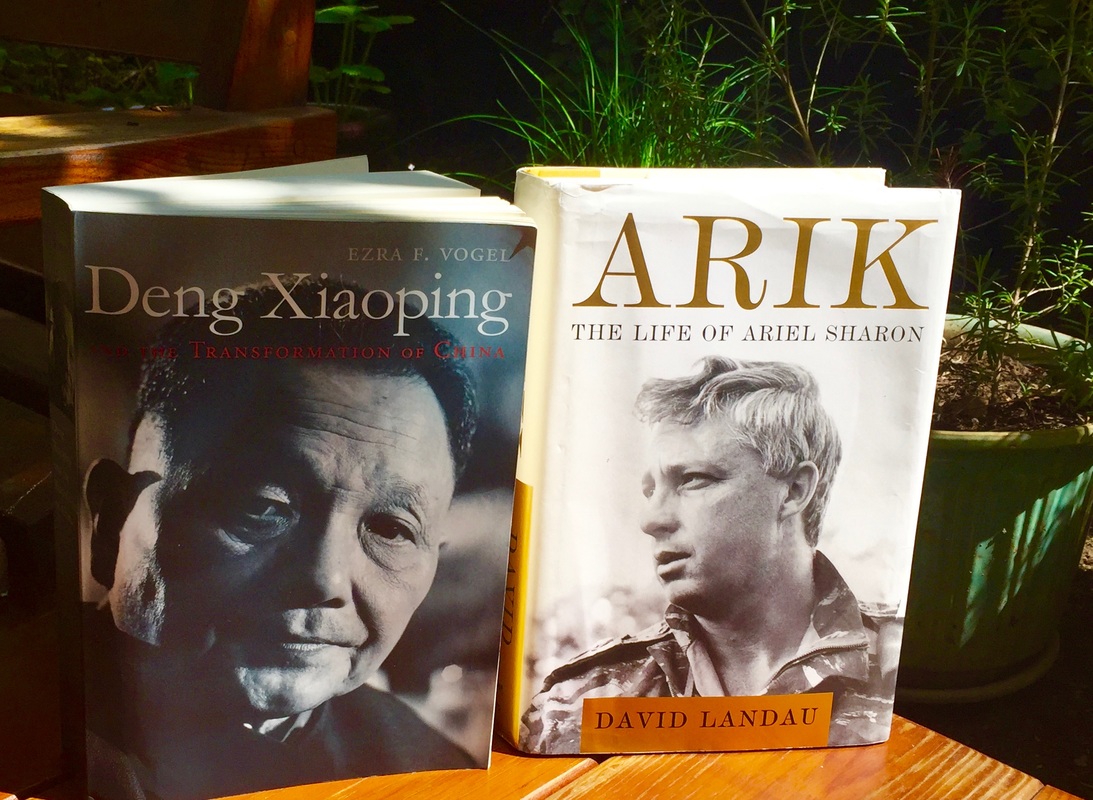

It is surprising to some extent to see how the world these days devours ‘self-help’ and or ‘career advisory’ books, all promising to deliver the right tools and techniques to bring us riches and happiness or some sort of combination thereof. It was a relief for me this summer to return to my old passion of reading political biographies and to realize that all the clues to happier lives and better careers can easily be found by studying the lives of some of history’s great and see how they navigated some of the deeper challenges that defined their lives and come out as winners. So this summer I dove into David Landau’s epic work on the life of Ariel Sharon and it was followed by the deeply researched and voluminous biography that Ezra Vogel put together on Deng Xiaoping. As a historical figure, Sharon tends to generate some negative reactions given the abrasive style he was known for, his presumed guilt in the Sabra and Shatila massacres and triggering the second intifada following his visit to the Temple Mount in 2001. Both of these claims by the way are clearly and helpfully dispelled by Landau’s book. Deng however usually can count on a far more sympathetic treatment as the man that transformed and modernized China. This of course is somewhat questionable as Deng most probably had been far more directly involved in unleashing lethal force, on his own subjects no less, during his career as one of Chairman Mao’s key enforcers and eventually as China’s paramount leader. During my years in Asia it was not unknown to hear business leaders praise the bloody crackdown in Tiananmen as one of the essential building blocks of a stable China that is open for business. Whatever the merit of that morally flawed argument, both Deng and Sharon built their careers in newly formed nations – Israel being established in 1948 and the People’s Republic of China only one year later, 1949 – that were under such formative pressures that the internal and external use of force were essential parts of the job. Although China and Israel came into being under vastly different circumstances and cannot be compared in terms of size and histories, the parallels between the careers of both men are striking. Both biographies clearly present that their entire lives were essentially in the service of their nation and that both consequently took a deep personal toll in the process. These were compounded by significant personal dramas. Landau’s description of the death of Sharon’s young son Gur is moving and heartbreaking, much the same can be said for the way Deng’s son Pufang was denied medical treatment during the Cultural Revolution a result of which he spent the rest of his life in a wheelchair, paralyzed from the waist down. It is a testament to the quality of the books that you can sense how the deep pain of these personal tragedies accompanied these two men for the rest of their political lives and how it motivated them. Yet the essence of both careers was that it took a lifetime to get to the top positions, Deng being a solid seventy-four when he could truly claim to be China’s paramount leader, Sharon was seventy-three on the day he was inaugurated as Israel’s prime-minister. Both books give a very detailed accounting for the reasons it took so long and how both men persisted against the many different forces that were aligned against them. The pragmatic fixer Deng had the nearly insurmountable task to carve out a space for plain reason and common sense progress in the toxic environment created by Mao’s continuous political struggles where dogma trumped everything else. Deng was purged from the leadership twice: in 1966 and within about a year of returning from the first one, in 1976. Both of these had career ending potential, yet Deng not only overcame both events, he emerged stronger and far more decisive. Sharon in turn had to navigate a different but equally explosive political environment in Israel – Landau’s book is a key primer to get a feel for the machinations of Israeli political power-play – but also his own character which at times created some roadblocks on avenues that had opened up for him. The benefit of the long road that both had to travel was of course the accumulation of deep experience and a huge personal network of politicians, administrators and military commanders complemented by an incredibly clear and growing sense of direction for each nation. This of course was compounded by the fact that by the time they reached the highest office there was little time left for them given their advanced age. For Deng it meant rejecting orthodox communism and embracing capitalism while maintaining one-party rule, for Sharon it was ditching the nationalist settler movement that propelled him to power and embrace disengagement from the Palestinian enemy. Once you come to the end of Sharon’s biography it is both harsh and painful to see how he in early 2006 succumbed to a hemorrhagic stroke that sent him into an eight-year coma from which he never woke up. The remaining question that even the masterful Landau can not answer is whether Sharon would, following the departure from Gaza in 2005, have continued his unilateral disengagement by withdrawing from the West Bank and setting the stage for more favorable conditions for Israeli-Palestinian peace than is the case now. What we do know is that had Sharon lived as long as Deng, he would no doubt have left an even deeper imprint on the Middle East. Deng retired from the political scene in 1992 having reached the tender age of eighty-eight and as opposed to Sharon, did live to see most of what he set out to do: a stable and steadily growing China. So what do these old men of state and their biographers have to tell us about our lives and careers? The same lessons that drove Deng and Sharon to ultimate success in their lives and careers. Hard work, focus, family and never ever giving up. Note: Deng Xiapong and the transformation of China by Ezra F. Vogel (2013) and Arik: The Life of Ariel Sharon by David Landau (2014). As a complement I would recommend reading The Cultural Revolution: A People's History, 1962-1976 by Frank Dikötter (2016) which gives a bit more depth and analysis of the horrors of the Cultural Revolution an area on which Vogel’s book was a bit light. So in many ways my life and career are a direct result of British engagement with Europe. In anticipation of the formal 1992 creation of the European Union, British banks started to evaluate their continental strategies and some, for the first time, embarked on recruiting graduates from across the channel. By sheer coincidence I ran into Barclays Bank at a job fair – not coincidentally in Brussels – and was asked to apply for their European Management Development Program. I did and so my first job application landed me right in the City of London, learning the ropes of banking at one of its more venerable institutions.

The interesting thing was that my new British colleagues ridiculed their nation’s and their employers’ European project and where somewhat miffed at all the opportunities and goodies that were thrown in the direction of the bank’s ten ‘Euro-recruits’. From day one I was lectured on the conspiracy coming from Brussels to subvert British freedoms, abolish pound sterling and eventually dismantle Westminster. This was long before immigration concerns and Nigel Farage. These were the last days of Margaret Thatcher whose career essentially ended over her views on Europe and the infamous campaign by The Sun newspaper to dispense some advice to the President of the European Commission on where to put his European Currency Unit as it was called in those days. Having grown up in a nation devastated by World War II where European co-operation was essential to economic recovery, there was never any debate, discussion, let alone an inkling that there might be something negative to say about European co-operation and integration. On the contrary, the late 80s were a time when the advent of the single market would bring more freedoms, riches and success for those that participated in it and my instant recruitment into London was the undeniable evidence of that. Critical thinking about the European Union was non-existent. Imagine my initial surprise at the British bitterness about it all. That said, it did change my thinking and my crash course in Euroskepticism allowed me to see that giving up your currency would mean giving up your ability to be the master of your own destiny as Greece has now painfully learned. Globalization is great and opens the door to many opportunities, but to hand its management to unelected bodies far removed from the nation state will inevitably open the door to some unintended consequences. Even with Thatcher disappearing from the scene, the debate in Britain raged on. And now, some twenty-five years later that British suspicion about the entire project has invaded many parts of continental Europe and has been adopted by emerging political movements on both the left and the right. Deep frustrations over unrestricted immigration and the economy at large are turbocharging populist sentiment and the EU is the first in the line of fire as an establishment project seen to have been instrumental in undermining the safety and security blankets that many across Europe had come to take for granted. Protest and anger are thus not only informed by evidence, but equally by ‘nostalgia’ something populist politicians love to plug into. So the Brexit vote should not come as a surprise at all despite the near hysteria that enveloped the media and markets almost immediately after the results were confirmed. The consequent demise of both David Cameron and Jeremy Corbyn were also long in the making, the Brexit vote just accelerated it. And as such last week’s events should be welcomed as a timely wake-up call for Europe to come to terms with deep economic shifts, nearby war and chaos (Ukraine, Syria) and the festering wounds inflicted by harsh monetary policies, again Greece, but who is next? European commissioner Frans Timmermans today on his Facebook page admitted that the time has arrived to be ‘brutally honest’ and that the Brexit vote is a symptom of the feeling that ‘we have lost control of our destinies’. As much as the vote shook up Britain, it will give an equal boost for re-examination in Brussels. So that is why we should welcome what happened in Britain last week. Although there will be quite some chaos in the weeks to come, think financial turbulence and purges in the British Labour and Conservative parties, there will and has to be a way out of this mess. It will consist of finding a ways to re-establish British relations with Europe, which will neither end nor remain the same, but more likely and hopefully will find some new middle ground. Britain cannot afford to let a referendum – a terrible tool to set a political course at the best of times – determine its future direction. Once the internal bloodletting is done, possibly followed by a general election, serious discussions can start without invoking the dreaded Article 50, which will set a timetable for a British exit. This process will help Europe find its balance and involve some serious re-examination on issues such as centralized governance, immigration, security and macro-economic policies. Yes, I refuse to believe that Britain is out and that we are headed for some sort of dark age. But even if that were to happen there will be a route to some new equilibrium. Things will not be easy, but at the very least we are all awake now and ready to participate in framing a new future for Britain, Europe and the world at large. My induction in global thinking decades ago in London does not allow me to believe otherwise. Postscript on July 7, 2016: it is of course quite extraordinary and maybe not coincidental that one of the very colleagues I referred to here and with whom I worked together in my first year at Barclays is none other than Andrea Leadsom (née Salmon), one of the two remaining contenders for the conservative leadership. Or how to compare the two different House of Cards trilogies So on Friday night we got right into it and knocked off the first two episodes of House of Cards, Season 2. A good start with a driven and scheming Frank Underwood, but as was the case with season one, thoughts inevitably wander back to the original FU, British prime minister Francis Urquhart. And begging the question, who is the better one and if there isn’t one that is better, how do they differ and why? Having just started the second season it is of course not possible to render a fully baked verdict, but there are some notable differences between the American and British Francis. The latter, a living monument to the phenomenal acting talents of the late Ian Richardson, was in political terms a staunch Thatcherite. In fact, the series creator Michael Dobbs has been rumoured to have coined the name ‘FU’ after meeting the late iron lady in person. Underwood, the Democrat is devoid of any deep ideological urges and is more of a Clintonesque power broker willing to cut any kind of political deal in order to advance his career. A battle with the teacher’s unions in the first season ends with a bill that ultimately satisfies most parties with Underwood taking credit, Urquhart in all likelihood would not have rested until he had personally reduced the union to a pile of human rubble. From that perspective both series reflect the political era in which they were created, Urquhart coming out of the polarized eighties, whereas Underwood stands atop the centrist model that has framed the Clinton-Bush-Obama-Clinton era. One of the other key differences between the two political maestros is related to that. Urquhart’s is indeed not a nice guy by any means, in particular when he addresses the viewer directly to elaborate on his dire views of humanity and his political friends and foes. He in fact is a very lonely and bitter warrior whose disdain for the world around him makes him seriously unlikeable. Underwood however comes across as a kinder and gentler soul, precisely when he talks to the audience and you find yourself thinking, yes, that somehow makes total sense. A drinking spree with former college buddies in season one and trying to neutralize Raymond Tusk’s influence on the oval office give Underwood a human and sometimes almost admirable foundation, something utterly lacking in Urquhart’s cold world. The notion of a nicer Underwood is also supported by the sort of victims he makes. The ambitious Zoe Barnes will get on your nerves as a not particularly likeable journalist, and it is quite hard to warm up to late congressman Peter Russo. Yet to this day I have warm feelings for Zoe’s British equivalent, Mattie Storin and recall the brutal way Urquhart dispatches her when he throws her off a Westminster roof. The viewer is upset and misses her, but it is hard to feel the same about Barnes and Russo. Simply put, Urquhart is the crueler politician and Underwood’s creators must somehow have positioned it that way in the script. Yet it does not make Urquhart unlikeable. Far from it. The acceptance of evil as a viable tool to heal the nation and further one’s career is given wings by the classic parody of Westminster politics that the British version of the show is. Nowhere is that better exemplified than in the second season entitled ‘To Play the King’ where Urquhart takes on the constitutional monarch, a thinly veiled caricature of Prince Charles who has just ascended the throne and wastes no time to implement a more social and caring agenda, putting him on a direct collision course with our hardcore capitalist Urquhart. The battle of inherited privilege versus the fearless commoner, a role Urquhart masterfully assumes, somehow gives the prime minister the upper hand in the demise and forced abdication of the new king, resulting in this classic scene: To Urquhart in the end it all is a game, playfully moving from target to target with a wink and a nod only to accumulate more power. Inflicting deep loss and ridicule on his victims is an integral part of this mission and he accomplishes it with verve and style. To the audience it is a hilarious way of commenting on the realities of political life as we understand them and therein probably lies some of the respect we ultimately extend to Urquhart. Despite all his brutal tactics he has a point. With Underwood that is far more difficult to establish, it is almost as if there are no deeper truths or wry commentary that the viewer can take a way from the southern politician. Underwood at times is bland and reluctant to mock and criticize the foundations on which present day Washington power broking is built. He is a willful part of it all and Americans take it the way it is. Carried by Kevin Spacey it makes for great drama, but it lacks the punch of the British House of Cards.

Above all it is the ability of the Brits to distance themselves from the subject to assess its inherent weaknesses and shortcomings while talking real political issues. “To temper economic rigor with a little more respect for human values” as the embattled monarch in the second season states – against Urquhart’s explicit wishes - is as real an issue today as it was in the eighties and nineties. It elevated the original House of Cards to a benchmark in political drama that will stand the test of time. The American version is as dark but in its delivery a lighter version of the original. That said, you have to work hard to keep the urge to binge watch under control, because House of Cards Season 2 is a riveting experience. |

Archives

April 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed