|

A few weeks ago, Michel Bacos passed away at age ninety-four. It got some media attention, but not more than a few small obituaries and twitter references. I briefly mentioned it, but this week a video snippet of his funeral service appeared online and it prompted me to write about the man and his actions in a bit more detail.

Bacos had a colourful life. French, but born in Egypt, he fought during World War II and went on to become a pilot for Air France. In that capacity Bacos found himself as the captain of the ill-fated Flight 139, which on June 27, 1976, was scheduled to fly from Tel Aviv to Paris with a short stop over in Athens. There, a gang of German and Palestinian terrorists boarded and hijacked the plane and directed it to first Benghazi in Libya and eventually to Entebbe in Uganda. The plot thickened there. It turned out the hijackers were getting strong support from then Uganda dictator Idi Amin. Over the course of a few days the pressure was turned up as the terrorists sought not only a dollar ransom, but the release of a large number of Palestinian terrorists imprisoned in Israel. It put the government of then Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin in a very difficult spot given its stance on non-negotiation with terrorists and the long distance to Uganda made any rescue attempt next to impossible. After only a few days, the crisis worsened as the Israeli and Jewish passengers were forcibly separated from the rest of the travellers, resulting in scenes reminiscent of the Holocaust. Not long thereafter, the non-Israeli contingent was released. At that point captain Bacos and his crew were given the option by the terrorists to leave too, but Bacos did not even consider it for a second and opted to stay with his passengers. He did give that option to his crew, all of who unanimously agreed to stay on. Given the likelihood of a very bloody ending to the affair, an extremely brave and commendable move and one that would put Bacos in the history books. The captain himself did not think that much of it when he commented later: “There was no way we were going to leave – we were staying with the passengers to the end,” he said. “This was a matter of conscience, professionalism and morality" After all diplomatic efforts had been exhausted, the Israeli government launched one of the most daring rescue operations ever, liberating the hostages and crew, killing all of the hostage takers as well as destroying a significant portion of the Ugandan air force. During the operation three hostages were killed, as was one of the Israeli commandos, Yoni Nethanyahu, the older brother of the current prime minister. One passenger, Dora Bloch, who had been evacuated to a hospital prior to the rescue mission was subsequently murdered by Amin's security forces. Bacos was honoured across the globe and his resumed work as captain not long after the drama, insisting his first flight back on the job would be to Israel. His heroism and the natural way in which he assumed full responsibility for his passengers under the most adverse circumstances are of course deeply commendable. It made him a hero and an example how to keep the moral high ground, even in a situation where you may not get out alive. But at a deeper level there is more to the move Bacos made. What he did was essentially what most Europeans failed to do during the Second World War. Taking a stance and doing the right thing when ordinary Jewish citizens are being singled out for death just because of who they are was exactly what was lacking in most of Europe. And it was exactly that which contributed to the death of six million Jews. Bacos must have sensed his actions had a far deeper meaning beyond just acting morally during a plane hijack. He may never have found the right way to express it, but if you see the short video of his funeral you sense what is going on. You see French flags, a priest, some French veterans, but you hear a national anthem that is not French at all. The anthem was played at Bacos’ own special request and it is the one national anthem that expresses hope. The hope.

0 Comments

How the story of diaspora and determination entered my life and how it fascinated and inspired

My love for books must have originated in my dad’s study. Many hours I spent there flipping through his shelves were I could find anything about history, psychology, geography, biology, and of course war. Lots of war. As a teenager growing up in World War II it had framed his world, his thinking and he kept reading about it until his last days. It was a deep search for the ‘why’ and the ‘how’ and the more books and studies appeared over the years, the more sources there were to try and figure out that question. Amid all of the books there was one thick volume that showed victorious soldiers in a desert like landscape, all smiling and all in color. As I must have been five or six I was able to organize events based on the color or black and white nature of the photos, and the cheering soldiers were not from the 1940s. It fascinated me although I could not pinpoint why they were so happy and where exactly they were. The black-and white shots in other books were far more gruesome. Emaciated corpses, gallows, kids rounded up by armed uniformed men and the haunting photo of young men chased down a Dutch street by – that much I had learned by then – German soldiers. Over the decades that followed the story of the Holocaust unfolded for me and the razzia on the Jonas Daniel Meyer Square in Amsterdam in February 1941 would go into history as one of the first and more brutal exercises of Nazi persecution in the occupied nation. Of the 427 men rounded up that day most had died under horrific circumstances by the summer of that same year in the Mauthausen concentration camp. The contrast of the cheering soldiers and the terrified young men was telling. Seventies Life in the early 1970s in The Netherlands was, by all accounts, great. The restored economy after the war had started to pay its dividends, economically and socially. The age of flower power influenced middle class life and open liberal norms where an integral part of the left’s steadily growing influence, the ruling Labour Party was above all, perceived to be cool. And the Dutch punched way above their weight internationally: calling out the Greek colonels, protesting against Pinochet in Chile and against the fascist regime that was still governing Spain under General Franco. As fierce as the government and the many activists were about transgressions against human rights in said countries, as deep was the love for other states. Passion and support for the young state of Israel, barely twenty-five years old in 1973, constituted an article of faith in the lowlands during the seventies. I still recall the emotional embrace between Dutch Prime minister and Labour leader Joop den Uyl and his Israeli counterpart, Yitzhak Rabin. There was a deep love for Israel and during the Yom Kippur war a local artisan store in my hometown raised funds to send to the Jewish state, it was only natural that we as kids found a way to contribute a few coins to this noble cause. A small nation, up against a massive force of Arab nations armed by the Soviet Union put Israel in the position of the underdog. They could and should count on our support. And although it is hard to make the retroactive argument, we must at the time have sensed that Israel was given a shot not just because it was an underdog and a fresh young nation. Its birth and fight for survival in all likelihood carried a dark part of our own Dutch history that had to be redeemed. The Visit As deeply rooted I was in Dutch culture my yearning for the outside world was big. America was light years away and my dad’s business trip to New York was a community event that we talked about for weeks. China was even further away and we were led to believe that Mao had figured out socialism and that the Chinese were happy denizens in their monotone outfits. Too young to understand but having the right age to be fascinated by the foreign, I yearned for everything from outside our borders, the more exotic the better. It was in this context that our fairly progressive school implemented a weekly program of folk dances, from grade one to grade six. It was of course awkward in the beginning, but gradually we got the hang of dancing for a few hours each week, opening our world to new rhythms and foreign cultures. The dance teacher turned out to be a man of the world and had organized the visit of an Israeli dance group to our town, including a performance at the school and some homestays for the young Israeli dancers. As luck would have it, my mom served on the school board and invited the group’s leadership team for a dinner in our house. Seated next to the wife of the group’s leader, Ruth, I was taken in by what these tough and Mediterranean looking people brought into our lives, arguing loudly with each other and with their hosts. It fulfilled my need for the exotic and the more exciting things the world had to offer. The group’s leader was a quiet man and most of the attention went to his radiant wife and the lead singer in the group, Effi Netzer who as I later learned was and still is one of Israel’s pre-eminent folk singers. There were also a few men that tagged along with the group and their role was not all that clear. They hung around the group in a disinterested way and had no creative responsibilities and I recall the ongoing debate among us kids, wondering what Gil, Dov and Moshe were up to. It was my father in the end who undid the magic but managed to up the fascination with the entire visit by disclosing that these were armed security people. He could of course not resist mentioning that they were ready ‘to go’ if any threat to the dance group would present itself. The conflict in the Middle East had somehow made its way to a sleepy Dutch suburb, some excitement, at last ! Connecting the Dots All these impressions started to merge and make sense in one way or another as the threads provided by the horrors of the Holocaust merged with the unfolding story of the state of Israel. As impressed as a young kid can be with armed security forces in the house, it was the realization that our visitors had no other option than to bring their own protection to the table wherever they traveled. It was clear, even then and at that age that no one else would really bother to ensure the safety of travelling Israelis. On the contrary, in the few instances that they had realistically expected to rely on foreign security it had failed miserably, the wounds of the massacre at the Munich Olympics in 1972 were still fresh and raw. So I began to stich the pieces together and after reading Leon Uris’ books Exodus and Mila 18 as well as Dominique Lapierre and Larry Collins’ ‘O Jerusalem’ the picture of Israel’s emergence became clear. A home for a persecuted people who had been given no other option than to fend for themselves, where and wherever they were, conquered meter by meter, shedding lots of blood. From expulsion to diaspora to holocaust to redemption through statehood, the Jews had been able to overcome the deepest misery history had meted out and had returned to their ancestral lands some two thousand years on. And the cheering men in the book in my dad’s office were Israeli soldiers who had recaptured Jerusalem during the Six-Day War of 1967. The story of Israel represented a form of determined self-reliance that for us as post-war, young and relatively complacent Western European kids was hard to fathom. It was exactly what it made so appealing. What for Israelis was an inborn need for survival was for us something we could only hope to strive for. What became even clearer was that the terms Israeli and Jew are interchangeable. Many Jews - in fact most of them – were not Israeli, yet they are part of the same tribe. If there was any doubt about this it was not long after the visit of the dancers that on a hot summer day through the open windows in our neighbourhood I could her radios announcing how Israeli commandos had liberated Israeli and Jewish hostages at the faraway airport in Entebbe, Uganda. They were saved from likely mass execution by terrorists. While most passengers had been released after a number of days, the terrorists had ensured to separate all Jews from the other passengers. For those not up to speed of what happened at that faraway African airport, I encourage you to Google the name of Dora Bloch, and read on from there. Israel’s bold military move delivered the exact evidence of the self-reliance that Israelis had to exercise in order to survive. For when it came to the crunch, the rest of the world either did not care or were too conflicted to take a position in what appeared to me to be a very simple ‘good’ versus ‘bad’ scenario. Baffling as it was, the UN found room to criticize Israel for violating Uganda’s airspace (remember Kurt Waldheim?) and Air France captain Michel Bacos who had remained with the hostages when given the option to go also came under fire for reasons no sane human being could possibly comprehend. It was all evidence of an incredible double standard against which Israel – and Jews in general – were measured, something that continues to this day in each and every international venue. Guilt As time wore on the contours of the Holocaust started to become even clearer with online testimonies of survivors and newly found documents in archives across Europe. We had dutifully learned that it all was the work of one madman whose extreme racist views swayed a nation down a troublesome path of mass murder and eventual self-destruction. Yet we had to make some effort to find out that, what Hitler did was simply activating the deep undercurrent of anti-Semitism long existent before his emergence as a political force in Germany. And not just Germany, I might add. And although the Dutch could claim some high ground as having opened our doors to Jewish refugees throughout the centuries – proudly marketing Baruch Spinoza and Anne Frank as ‘Dutch’ wherever possible – most of Europe was drenched in deep anti-Semitic sentiments. The fact that Christianity finds its roots in the worship of an errant Jew who had challenged the orthodoxy of his nation’s beliefs and found death on the cross at the hands of the Romans whose hand in turn had been forced by the local Jewish clergy, did not help. It took the Dutch nation to this day to acknowledge the pitiful and regrettable role it played in the persecution and death of some 102,000 Jewish citizens as rounding up the young men at the Jonas Daniel Meyer square was just the start. It was something that was conveniently swept under the carpet during our history classes and the fact that there had been some Jewish survivors was presented as evidence of the heroic efforts of the Dutch resistance. For instance, it was not until 2011 that Ad van Liempt’s book about the complicity of the Dutch police in the deportation of those Jews unveiled the fanaticism and depravity that was put on display in facilitating the Nazi occupier’s dirty work. It was a nauseating read. Again, Dutch guilt more than anything else was what drove this ‘special relationship’ with Israel. Crossroads Israel’s confidence and successes grew under holocaust survivor Menachem Begin who inked the nation’s first peace deal with Egypt and who had the clairvoyance to neutralize Iraq’s emergence as a nuclear threat by bombing the reactors in Osirak. The latter was seen as an act of aggression but by most objective standards, a sensible pre-emptive act. Israel had by the early eighties transformed itself from a young and threatened nation to a confident power player and the correlation between success and worldwide criticism manifested itself strongly after Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982. And although Israel was absolved of the relentless criticism over the atrocities during that war – read Dov Landau’s phenomenal biography of Ariel Sharon – a questionable pattern had been set. The love affair with the young state had started to show its cracks and I clearly recall how among the late teenagers that we now were I had to outline the justifiable and rational underpinnings of something the rest of the world considered an unjust war. No, the invasion of Lebanon was not a pretty affair, but nor was lobbing missiles into Israeli schools located in northern Israel. However inspiring the story of Israel’s birth and early years was to some, geopolitical realities framed the nation’s successes much differently. The ‘Arab oil tap’ and the steadily growing Muslim population in European cities would shift attention and respect away from Israel at a time when its underdog status had long evaporated. The old contours of anti-Semitism started to emerge again after an absence of only a few decades. In recent years it seems to have been unleashed in full force, note for instance how the leader of the British Labour Party recently found himself embroiled in a scandal for supporting the very sentiments we had all thought had disappeared from mainstream political discourse. It is not a coincidence that Israel’s current prime-minister, Nethanyahu has often said that what is left of European Jewry should pack up and come home to Israel. It is indeed sad that in a city that appeared to have successfully resurrected itself from the horrors that took away most of its Jewish citizens, anti-Semitism is back as part of daily life in the city. A city whose name in Yiddish designates a ‘safe place’ something it really wasn’t in the end. As a kid I grew up not only in my dad’s study learning about the Holocaust, Jews and Israel, I grew up with people that hardly ever used the word Amsterdam. They just called it what it was supposed to be, a great and safe place: Mokum. Then and Now The scene in our little school was breathtaking. Some thirty Israelis in their early 20s performed dances and song in the school’s central hall and the place broke down under the incredible energy, thrill and boundless enthusiasm. We as kids went crazy, clapping and cheering, we had never seen anything like this before in our lives. It was as if rock stars had descended upon our little school. The dances apparently were just the start as we were promised a solo performance by the group’s female lead singer. The announcer, probably forgetting he was at an elementary school, could not restrain himself – nor could we – over her incredible beauty. Tanned with dark hair and on seventies-style high soles, Haya Arad banged out a song that many years later with the help of Google and Spotify I was able to discover was the Nurit Hirsh & Ehud Manor classic, Ba-Shanah ha-Ba'ah. She performed it as if she were a big star in a major venue rather than a Dutch school with some kids and teachers and parents clapping and singing along. We all went into some frenzy and the school was shaking, this was music, this was singing ! The show finally was tilted to a different level when folk singer Effi Netzer took the stage with his accordion and urged everyone to sing long with a self-composed catchy tune. To this day I can sing it and realized it revealed the deepest aspirations of all of Israel: Time will come, hear and say Peace is yet on its way Together and never apart Sing this song with all your heart This was followed by a never ending Halellujah, Hallelu, Hallellujah, Hallelu …. “ When the group left, the now celebrated security men in tow, we begged them for signatures and encircled the bus so it took them quite some time to make their way back to the airport. The event sealed a love affair and a hope that whatever was in store for Israel, we all hoped for it to be the very best. More than anything, the story of the Jews and their hard fought journey back to Israel impressed upon me the virtues of self-reliance and determination against all odds. But there is also a component of guilt as our post-war generation had escaped the worst ravages of history and was given access to a seemingly carefree world. And maybe even some envy, because what if history came back and it turned out that we were totally unprepared for dealing with it ? The latter question may be answered in decades to come and in that process, what better to do than pass these lessons from history on to your children? Photos Top: Flags outside the Menachem Begin Heritage Center in Jerusalem Center: The razzia on the Jonas Daniel Meyer square in Amsterdam on 22 en 23 February 1941. And: a stone’s throw from the Israeli-Egyptian border near Eilat, my two daughters and a Dutch-Israeli friend unaware of the meaning and history that this photo represents, they just had a great time snorkelling in the Red Sea.

Some lessons for life and political success: staying at it

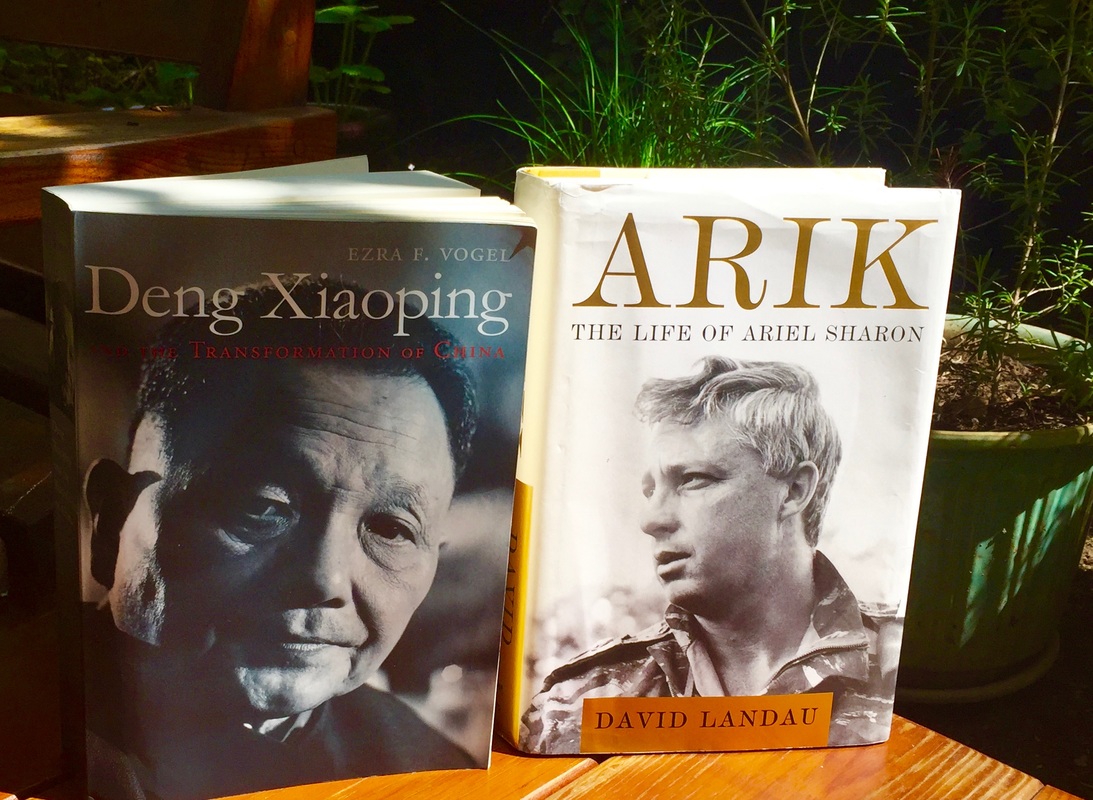

It is surprising to some extent to see how the world these days devours ‘self-help’ and or ‘career advisory’ books, all promising to deliver the right tools and techniques to bring us riches and happiness or some sort of combination thereof. It was a relief for me this summer to return to my old passion of reading political biographies and to realize that all the clues to happier lives and better careers can easily be found by studying the lives of some of history’s great and see how they navigated some of the deeper challenges that defined their lives and come out as winners. So this summer I dove into David Landau’s epic work on the life of Ariel Sharon and it was followed by the deeply researched and voluminous biography that Ezra Vogel put together on Deng Xiaoping. As a historical figure, Sharon tends to generate some negative reactions given the abrasive style he was known for, his presumed guilt in the Sabra and Shatila massacres and triggering the second intifada following his visit to the Temple Mount in 2001. Both of these claims by the way are clearly and helpfully dispelled by Landau’s book. Deng however usually can count on a far more sympathetic treatment as the man that transformed and modernized China. This of course is somewhat questionable as Deng most probably had been far more directly involved in unleashing lethal force, on his own subjects no less, during his career as one of Chairman Mao’s key enforcers and eventually as China’s paramount leader. During my years in Asia it was not unknown to hear business leaders praise the bloody crackdown in Tiananmen as one of the essential building blocks of a stable China that is open for business. Whatever the merit of that morally flawed argument, both Deng and Sharon built their careers in newly formed nations – Israel being established in 1948 and the People’s Republic of China only one year later, 1949 – that were under such formative pressures that the internal and external use of force were essential parts of the job. Although China and Israel came into being under vastly different circumstances and cannot be compared in terms of size and histories, the parallels between the careers of both men are striking. Both biographies clearly present that their entire lives were essentially in the service of their nation and that both consequently took a deep personal toll in the process. These were compounded by significant personal dramas. Landau’s description of the death of Sharon’s young son Gur is moving and heartbreaking, much the same can be said for the way Deng’s son Pufang was denied medical treatment during the Cultural Revolution a result of which he spent the rest of his life in a wheelchair, paralyzed from the waist down. It is a testament to the quality of the books that you can sense how the deep pain of these personal tragedies accompanied these two men for the rest of their political lives and how it motivated them. Yet the essence of both careers was that it took a lifetime to get to the top positions, Deng being a solid seventy-four when he could truly claim to be China’s paramount leader, Sharon was seventy-three on the day he was inaugurated as Israel’s prime-minister. Both books give a very detailed accounting for the reasons it took so long and how both men persisted against the many different forces that were aligned against them. The pragmatic fixer Deng had the nearly insurmountable task to carve out a space for plain reason and common sense progress in the toxic environment created by Mao’s continuous political struggles where dogma trumped everything else. Deng was purged from the leadership twice: in 1966 and within about a year of returning from the first one, in 1976. Both of these had career ending potential, yet Deng not only overcame both events, he emerged stronger and far more decisive. Sharon in turn had to navigate a different but equally explosive political environment in Israel – Landau’s book is a key primer to get a feel for the machinations of Israeli political power-play – but also his own character which at times created some roadblocks on avenues that had opened up for him. The benefit of the long road that both had to travel was of course the accumulation of deep experience and a huge personal network of politicians, administrators and military commanders complemented by an incredibly clear and growing sense of direction for each nation. This of course was compounded by the fact that by the time they reached the highest office there was little time left for them given their advanced age. For Deng it meant rejecting orthodox communism and embracing capitalism while maintaining one-party rule, for Sharon it was ditching the nationalist settler movement that propelled him to power and embrace disengagement from the Palestinian enemy. Once you come to the end of Sharon’s biography it is both harsh and painful to see how he in early 2006 succumbed to a hemorrhagic stroke that sent him into an eight-year coma from which he never woke up. The remaining question that even the masterful Landau can not answer is whether Sharon would, following the departure from Gaza in 2005, have continued his unilateral disengagement by withdrawing from the West Bank and setting the stage for more favorable conditions for Israeli-Palestinian peace than is the case now. What we do know is that had Sharon lived as long as Deng, he would no doubt have left an even deeper imprint on the Middle East. Deng retired from the political scene in 1992 having reached the tender age of eighty-eight and as opposed to Sharon, did live to see most of what he set out to do: a stable and steadily growing China. So what do these old men of state and their biographers have to tell us about our lives and careers? The same lessons that drove Deng and Sharon to ultimate success in their lives and careers. Hard work, focus, family and never ever giving up. Note: Deng Xiapong and the transformation of China by Ezra F. Vogel (2013) and Arik: The Life of Ariel Sharon by David Landau (2014). As a complement I would recommend reading The Cultural Revolution: A People's History, 1962-1976 by Frank Dikötter (2016) which gives a bit more depth and analysis of the horrors of the Cultural Revolution an area on which Vogel’s book was a bit light. |

Archives

April 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed