|

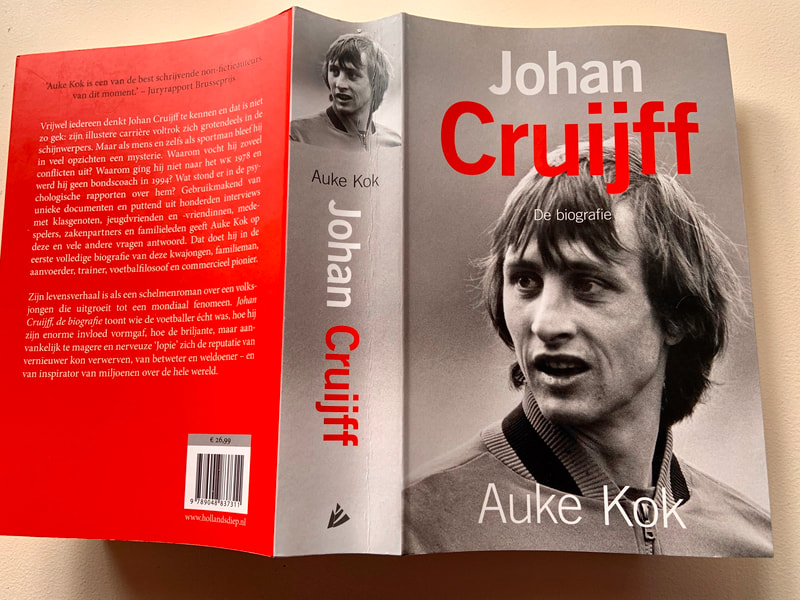

A great biography sheds further light on one of the world's best football players

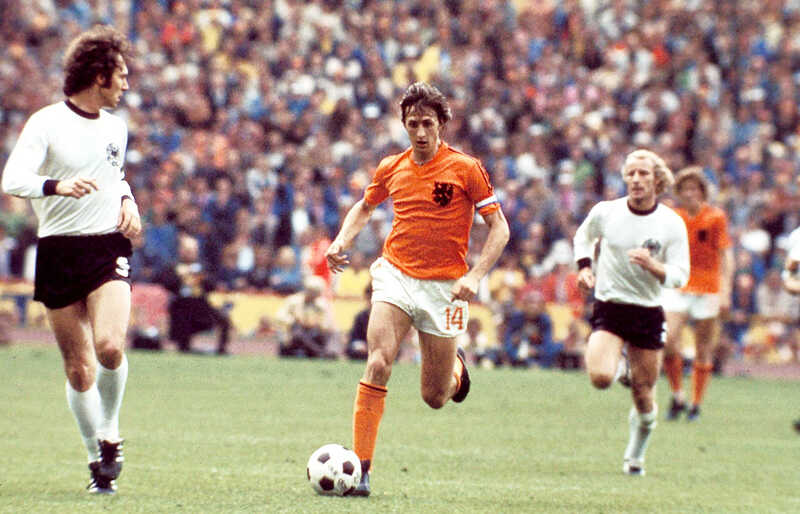

The debate as to who is the greatest football player will rage on forever, but the Dutch have long settled this question of course. Johan Cruijff (simplified Cruyff for international audiences) remains by far the best player ever and Dutch journalist Auke Kok penned a 640-page tome on the man who transformed not just the game, but also rose beyond it as an inspirational leader and individual who symbolized a new era of economic freedom and unprecedented individuality. The biography takes a few interesting themes and elaborates on these while following Cruyff’s career from childhood to his career start in the early 60s to his premature death of cancer in early 2016. The first theme is demonstrating the insane talent the man had as a football player, but noting that it would never have amounted to much had there not been a structure in which to display and use these talents. In the early 1960s, the years when Cruyff rose to prominence, Dutch soccer was an amateur sport, poorly organized and international results were practically non-existent. When Cruyff came on the scene at Amsterdam’s Ajax, the first attempts to professionalize the sport were only just underway and it was the emergence of Rinus Michels – who later was named FIFA’s coach of the 20th century – to lay the groundwork for disciplined football with plans, tactics and structure. It was in this framework Cruyff flourished as the increasingly well-oiled Ajax machine created the platform that enabled him to shine and lead in the delivery of three Champions League trophies as well as a World Cup for club teams. The Ajax model was replicated onto the Dutch national team which at the 1974 FIFA World Cup ended as runner-up, but with most of the world recognizing that the Cruyff-led side played the best football the world had ever seen. The duality of individual and team remained a constant throughout Cruyff’s career as player and coach, his brilliance could only shine in structured environments, but the clubs and teams on themselves would never have been able to shine without Cruyff’s brilliance. Kok’s book dives deep into the numerous conflicts and tensions that this dynamic generated, pointing to the successes it created, but also to the failures and missed opportunities. Cruyff’s deeply individualistic DNA just did not fit into any traditional structure. A similar dual dynamic underpinned Cruyff as person. Overly confident, intelligent, strong and at times arrogant, he was suffering from deep uncertainties and often used the weirdest rituals ahead of a game to quell the fears he suffered from. His uncertainty was most likely rooted in the early death of his father Manus and throughout life Cruyff tried to find a replacement for the father figure he missed since age twelve. But the uncertainty created by growing up in a family without a father manifested itself in a way that helped contribute to football’s rapid commercialization: Cruyff was almost paranoid about money and even as a well-established millionaire was suffering from deep concerns about his family’s security and well-being. This dynamic never played well in the Calvinist and sober Netherlands, many Dutch rolled their eyes over Cruyff’s hard and seemingly endless negotiations over contracts and commercial activities. However, if you read Kok’s book all of this was entirely logical in the context of Cruyff’s life and his awareness that he only had a short period of time to make money: Cruyff intuited economic uncertainty and was determined to be prepared for the worst. Despite his internal doubts, Cruyff always displayed extreme confidence and certainty in addition to an almost suicidal loathing of authority: many great career opportunities were destroyed in conflicts with referees, coaches and above all club directors. Any Cruyff fan – and I am certainly one – will attest that the deepest regret we all have is he never collected more than 48 caps for The Netherlands. A more pliant and collaborative Cruyff would have seen far more appearances in the Dutch national orange shirt and possibly more trophies and recognition. It seemed Cruyff accepted this outcome and in that provided evidence of his uncompromising personality. Financial certainty was there at his 50th when he stopped coaching altogether following a successful run at Barcelona. He focused on his charitable foundation and became a commentator on Dutch TV during which he appeared to elevate himself above everyone else with unfathomable analyses and remarks that became the staple of a number of books. “Football is simple, but playing simple football is very difficult” and “If I had wanted you to understand it, I would have explained it differently” became classics of Cruyff the philosopher. There was another dichotomy in his life: the consummate sportsman chain smoked throughout his career, something that no doubt contributed to cancer and his death at age sixty-eight. All his fans were devasted when his passing was announced and in particular the Dutch felt an incredible sense of loss. The pain was not just for a fallen sports icon, no, for a nation that had risen from the ravages of World War II, became an economic powerhouse and in the process had grown into a global vanguard of cool and hip individualism, it had lost the very symbol of that incredible rise. Born in 1947 and peaking in the 60s, 70s and 80s Cruyff had become the embodiment of that confident Dutch identity. The man himself understood exactly that he had already eclipsed earthly parameters by stating that “In some ways I am probably immortal”, a remark that opens the biography. And indeed Cruyff is immortal. His presence just in reading the book is weirdly palpable. His death ended one of most dynamic and creative eras in The Netherlands and in reading this excellent biography it lets you relive those days. At the same time, you learn from one of the few football players that transcended earthly life and became immortal.

0 Comments

|

Archives

April 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed