|

In only a few months time, I will be leaving on a mountain climbing expedition with Summits of Hope, the same group I scaled Kilimanjaro with two years ago. We will be attempting to summit Aconcagua in Argentina, the highest mountain in the world outside the Himalayas at 6,961 meters (22,837 ft) above sea level. I have started training and look forward to this great challenge, realizing it will be a lot harder than Kilimanjaro a few years ago. I will cover the cost for the entire expedition myself, but we are raising money for children at BC Children’s Hospital. Summits of Hope is quite different from other charities as all funds raised directly support one full-time position at BC Children’s oncology ward, cancer research, education and laptops/toys for children in the hospital. I’ve pledged to raise at least $5,000 in donations for this climb, but my goal is to raise more. This is the same amount I targeted for the Kili trip, but ended up raising over $11k thanks to many generous contributions. It is often surprising what people will contribute, really. Global News anchor Kate Gajdosik was part of this year's Kilimanjaro trip and here is a video of that prior to her leaving, and here is her detailed post on the climb and Summits of Hope's important role in it all. So if you would consider making a donation, take a look at my Summits of Hope profile page with a link to donate. Please make sure you select ‘Pieter Dorsman' as the climber you are supporting on the donation form and designate the amount that’s right for you, no amount is too small or too large. Tax receipts of course will be issued directly. For a donation of $40 or more, I will fly your message on your own personalized flag and we will send pictures of your flag flying on Aconcagua when we return. Selfie on Uhuru Peak, the summit of Kilimanjaro on October 17, 2013.

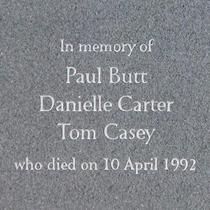

In the wake of the terror attacks in Paris, I remembered I once wrote a piece on the one terror attack that I ever experienced, or at least came relatively close to. This is what I wrote in 2003 about the 1992 attack on the Baltic Exchange. I made a few edits, but is largely the same text. And the photo of the damaged Commercial Union building above wqs made on April 13, 1992. It was in April 1992 when I was working in the City of London that I went on my first real business trip. For a young guy, a great milestone in an emerging career and the location was not bad either, Athens in Greece. It was a business development conference and that week, apart from the conference, was pretty much dominated by the very close election race back in the UK where the unexciting John Major eked out a narrow election victory over Neil Kinnock’s Labour Party. On Saturday morning as the conference wrapped up we heard the news that a big bomb had gone off in London’s financial district, the area where most of us worked. There were no clear indications of the exact location, casualties or damage other than that it had been a huge explosion. Those were the days before the internet and mobile, so we digested the news slowly and did not race to our laptops to have a complete minute-to-minute rundown of events. I stayed the extra day and when I got home on Sunday night one of my managers was on the phone shortly after my arrival asking me whether I had heard about the attack and how the trip to Athens had been. I summarized what I had to say quite briefly and let him know that I would give a full report of my trip the next morning. “Well, Pieter”, he said, “you are going to have a few days off because the bomb exploded at the Baltic Exchange and our office building is in such a shape that it is very unsafe for staff to return to work”. This was quite a surprise, our office was at the northern end of St Mary Axe, in fact everyday I walked right past the Baltic Exchange at the southern end of St Mary Axe, the place were the bomb had gone off. The next morning, the day off, I went to the area, camera in hand, and what I witnessed shocked and perplexed me completely. The area that had been damaged not only extended well beyond to what anyone would have believed knowing the location of the bomb; the damage done to that area, now cordoned off by police, was phenomenal. The impact of the explosion had covered the direct area with endless mountains of glass as nearly all of the windows of the adjoining Commercial Union skyscraper were knocked to smithereens. The force had also seriously damaged many other buildings, destroyed windows over a vast area, damaged cars and what amazed me and for some reason stuck in my mind: it left most traffic signs in a very wide area curved. The damage had thus also affected our building at the very end of St Mary Axe, although from the outside things did not look particularly bad. Apparently, there was significant damage and one of the greatest concerns was the structural damage not directly visible to the eye. Hence our few days off, in fact we spent the next two months in some reserve office space the bank had made available near St. Paul’s Cathedral. The background to the bombing was soon clarified. The IRA’s political affiliates, Sinn Fein, had lost a seat during the election (Sinn Fein did contest seats in Westminster but they never occupied them) and the heinous attack was a “punishment” for the conservative victory. Three people were killed and I remember very clearly that one of them was a teenage girl who had happened to be there, waiting in a car while her mother picked up her dad from work. I never directly linked the attack to myself or the chance that I could have been killed by it although the bomb went off right on the route that I walked every day from the Underground station to the office and back. I just did not happen to be there that day, I was in Athens, and there was, and is, no other way to look at it. During my stay in London Downing Street 10 had been attacked by a rocket propelled grenade launcher and one day the entire Underground system was shut down leaving my then girlfriend, and now wife, Irene presuming I was dead, however I was just four hours late being stuck in a bus somewhere on Piccadilly. At the time, the terror never felt like it was directed at me, or us, or to anyone close to me and I never got the sense from my British colleagues that they ever felt like they were a target. It was a constant, it was there, and if it came close to home it was sure to move on to another location. I never sensed fear, pain or worry. The nature, origin, much less a solution was ever discussed. The IRA was qualified as a group of isolated fanatics who did not even have majority support in their own ranks, losing a seat during the election was yet more evidence of their failure, isolation and increasing irrelevance. For me, it left a very vivid image of the physical impact of a bomb attack and it makes it easier to picture what can happen to people if they are in the vicinity of such a dreadful blast. Today, some twenty-three years on, with a settled conflict in Northern Ireland and a wave of new terror attacks enveloping Europe, it may be worthwhile to recall how the British in those days dealt with lethal terror. They adjusted a bit here and there, but carried on regardless. The other side of this of course is to remember those that perished, then and today, innocent bystanders in a pointless orgy of violence. Quite a few people have been asking about the ‘why’ of the terror attacks in Paris. Many others are shocked and surprised at the outburst of such extreme violence. For many however these attacks are hardly a surprise as they represent the most recent instalment of a process that got started in the 1950s with roots going back many centuries. Let me try and weave the component parts together into a narrative that I hope explains the ‘why’.

Collapse of the Ottoman Empire – It starts with the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire after the First World War where on the remnants of that empire a number of artificial states were created in the Arab-Muslim world. All of these states came to be ruled by repressive autocrats or families who were more or less aligned with the western powers that defeated the Ottomans. Autocratic Rule - These ruling elites largely survived through divide and conquer policies (think Sunni vs. Shi’ite groups in Iraq and Syria) or by closely aligning with the region’s dominant religion (think of the House of Saud as protector of the holy shrines in Mecca and Medina). Needless to say, these despots have used the most brutal and inhuman techniques at their disposal to consolidate their hold on power. Saddam Hussein in Iraq, the Assad clan in Syria, Muammar Gaddafi in Libya are some of the more recent examples here. Resource-based Economies - The abundance of oil (Gulf States, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Libya) prevented any form of economic or social innovation, the western petro-dollars kept flowing, creating a wealthy uber-elite that had no incentive to change, innovate or otherwise promote change to seek the betterment of their underlings. On the contrary, diversifying the economy would open the door to a level of foreign influence that could destabilize a hold on power that was tenuous at best. Many scholars have argued that an Arab world that at one point was highly successful and progressive reverted to anti-modernist stagnation. Channeling Resentment - Resentment and anger of the ordinary underlings could easily be channeled by directing tension and aggression to externalities. Israel was the regional bad guy to fight against, or the ‘other Muslim’ with the Iran-Iraq war that constituted the absolute violent low point in terms of intra-Muslim bloodshed last century. While this war of neighbours consolidated the ayatollah’s power in Iran and Saddam’s in Iraq, it created utter devastation for their citizens. Conflict with Modern and Secular World - Traditional Muslim life was challenged by modernity over the second half of the 20th century and as calls for progress through democracy were violently suppressed, a return to fundamental Islam (or Islamism) became a far more potent vehicle to challenge the westernized corrupt elites that governed the Arab world. Many have pointed to the Egyptian author and scholar Sayyid Qutb who emerged in the 1950s as a proponent of a return to tradional Islamist societies as a response to corrupt, westernized autocratic rule. Qutb is seen as the foundational ideologue of al-Qaeda and now, ISIS. Quest for Purity - As with most fundamentalist or totalitarian groups, the all-encompassing idea is to create a better world where the prevailing ideology provides a route to a pure and uniform society. In the case of Islam that meant a return to a form of government where the secular state and religious authority are merged into one and where Islamic doctrine governs day-to-day life. The best example of such an entity was the original caliphate of the 7th and 8th centuries. It also provided the antidote to the western model that separates church and state. Religion - And as opposed to fascism and communism where Hitler and Stalin banned or otherwise submerged religion, the religious doctrine in the fundamentalist mindset is the same as the political worldview to govern. When Hitler died fascism collapsed the next day, not so with Islam or Christianity for that matter as religion is far more potent than any secular worldview. It is outside the scope of my notes here, but the concept of God and the afterlife sets religion apart from any political ideology. Dissent and Religion Merge - So to go back to say the mid-1990s the dominant protest movement in the Middle East became radical Islam or Muslim fundamentalism, whatever term suits you best. The idea to resurrect the caliphate started to manifest itself violently and in pursuit of its goals severing the ties between the West and the Arab autocrats became one of its primary goals. It should be remembered that al-Qaeda under Osama bin Laden was able to emerge and grow in a fertile environment where first the Russians intervened in Afghanistan (1980s) and where the United States led a UN-sanctioned war against Saddam Hussein after he conquered Kuwait in the early 1990s. Attack the West, Provoke War, Weaken Local Rule - The 9/11 attacks completed the first phase of the process and the West’s response was exactly what al-Qaeda must have seen as its desired outcome: invasions in Afghanistan and Iraq, suppressing personal freedom in the West by creating a security state. All of these could potentially divide the West, weaken the local Arab autocrats and in time strengthen the hand of Islamists. The Quagmire – And that is pretty much what happened. The easy target was Saddam Hussein not only as a serial violator of UN resolutions, but Saddam himself had moved way too close to fundamentalism and organized terror in order to preserve his position which originally was far more pro-western and secular than the new make-up of the Arab world required him to be. So George Bush decided to remove him. Post-war Iraq was chaos and enabled local Iraqi fundamentalists under Abu Musab al-Zarqawi to create a foothold where western powers may have thought that a ‘fly-trap’ would get all radicals into Iraq where they could be defeated in a decisive manner. This did not happen and the United States beat a retreat, leaving a country in deep chaos under corrupt and sectarian Shi’ite rulers whose presence further strengthened the efforts of Sunni fundamentalists. Following Zarqawi’s death they re-emerged under the banner of ISIS. Arab Spring – All of this took place more or less around the same time of what came to be known as the Arab Spring of 2010-2012 where democratic uprisings (notably in Tunisia, Libya and Syria) saw a weakening of the old autocratic rule and a nascent democratic movement. But as we know now, opposition was not only channeled through believers in freedom and democracy, fundamentalists often gained the upper in hand in the revolts that emanated from that Arab spring. Noted examples are Libya, Syria and yes, Egypt, where a democratic experiment with a fundamentalist president (Mohamed Morsi) failed miserably. And there’s ISIS – So building on the groundwork of Qutb, al-Qaeda’s successes, the US failure in Iraq and its subsequent withdrawal, weakened Arab autocrats, combined with the emergence of newly energized fundamentalist groups provided the fertile soil for the creation of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) or now better known as ISIS. The Islamist Vanguard - As all revolutionary movements, be they fascist, communist, clerical or millennial in nature, a wealthier upper middle class vanguard establishes the way, think of the privileged upbringing Osama bin-Laden had or the background of Germany’s RAF terrorists. Or take Sayyid Qutb who studied in the United States, Colorado to be precise. They are the ones that conceptualize, create and finance the platform where the disgruntled troops can assemble and fight in pursuit of a better tomorrow, or in our case, a new caliphate governed by divine law. Alienated Converts - In the case of fundamentalist Islam, those initiators can draw on a large pool of potential converts, often than more than willing to take up arms and fight. They are essentially the unemployed or underutilized poor young men across the Middle East whose ranks have grown in a demographic boom that was never accompanied by an economic one. Add to this the very many Muslims across Europe (primarily Maghreb and Turkish influx to North and Western Europe) who are not only unemployed and underutilized, but alienated in a culture that is in all aspects diametrically opposed to the ones in which they grew up. Sexual Repression - And this brings us to the repressed sexuality in Muslim culture an element often overlooked but it stands to reason that it plays a crucial part in the emergence of fundamentalist violence. Traditional Muslim societies suppress both male and female sexuality and the resulting hormonal overdose for men can easily be channeled into violence. Let me give a simple example by pointing to that young and affluent Parisian couple where the girl is scantily dressed and both are enjoying a glass of wine in a trendy Paris bistro after a not so strenuous week at a local college or university. Their lives and values have been somewhat different, to say the least, from the single alienated Muslim youngster who empties his AK-47 on them. I hope this gets the point across. Europe - That brings us to Europe, at one point in the history parts of which were occupied by the Ottomans. The idea of the fundamentalists restoring their caliphate is fueled by the notion that its borders should once more extend to what they once were. Here the fundamentalist Muslim doctrine merges with nostalgic notions of a time past and of what could be tomorrow. Potent recruitment material. Is a European reconquest a real goal for ISIS? Hard to say, but in the current environment where the US has retreated, the north Atlantic alliance is at its weakest ever and where the Muslim segment of Europe’s population keeps growing in relative terms it is an attractive notion for ISIS to promote as part of its overall strategy of enlarging its domestic Arab footprint by severing the ties between Arab’s remaining autocratic rulers and European elites. Decadence and Freedom – And Europe (and America, Canada and Australia) represent the opposite of what fundamental Islam stands for: open and liberal gender relations, separation of church and state, increasing secularity (empty churches) and a general quest to enjoy life. We often see references from religious purists (not just Muslims, Christians too) to hedonism as one of the most abject expressions of life in Western societies. Any western city is now a perfect target and you do not have to necessarily bring in your recruits from overseas because they are already there. Paris has all of that and additionally a pretty terrible history with Muslims, few will recall the massacre of hundreds of Algerians in 1961 whose bodies were discarded in the Seine by the French police. More recently we can point to the cartoons published by Charlie Hebdo and the ensuing massacre at that magazine’s editorial offices. So what could be a more perfect target? It is outside the scope of this article to provide a solution to this deep and violent conflict. The core purpose is to explain in a short but hopefully enlightening way how we ended up in a world where a small group of terrorists can randomly butcher totally innocent people in a city far away from their ancestral homes. The most important thing to note is that there is no single and simple explanation like “if the United States had not invaded Iraq this would not have happened”. These are anti-intellectual short cuts that deserve no merit, as the reality is so much more complex. A number of things that I offer here may on their own not be solid evidence of contributing to terrorism, but together they constitute a narrative that may help us to understand the recent violence better. Anyone trying to find a solution will be perplexed by this complexity, which inevitably leads us to conclude that it will take a very long time before we can really address and solve it. An intellectually hollow campaign sets the stage for a transitional, but not an aspirational new leader

Only a few weeks ago I was sitting in the bus driving into Vancouver talking to two ladies who – by my estimate - were well into their sixties but still active in the workforce, commuting to work on a daily basis. As we crossed the Lions Gate Bridge passing two crowds waving Blue and Green signs, one of them focused on our political early morning chat. "You know what?" she said, “None of the parties are presenting a vision of the future … what do they really want for Canada?” It was exactly what I had been thinking throughout the campaign. No future aspirations, like addressing the question as to what will Canada look like 30 years from now. Or what given the enormous changes taking place internationally can we do and shape our place and role in the world? When I ran for school trustee about a year ago I discovered that talking about the future and about how to embrace change to create better opportunities does resonate with voters. It enables voters to see their role in creating change and to be part of that ‘better future’. It was what Ronald Reagan did so well, and why he was able to pull so many Democrats into his column: visionary politics transcend party politics. Yet, most elections in Western democracies these days have resorted to a low level debate about taxes, deficits and growth. And beyond that the only alternative offered is one of mobilizing the ‘fear vote’ or engaging with the ‘change vote’. Neither has substance and so we are treated to the usual smorgasbord of tax credits and incentives and broad references to ‘change’ and ‘security’. The problem with this is that the lives of most voters are not materially affected by a budget tweak here or a tax credit there. TFSA limits are largely irrelevant and working families are no better off by Conservative cash hand outs, Liberal tax credits or an NDP-driven childcare program that will never see the light of day because provinces will never pony up their part of the bill. The fact that some parties were arguing the country was in recession while it most likely was not, only proves this point. Odd as it may sound, the Conservatives were by and large the key offenders here. While Stephen Harper was right in defending his record and Canada’s economic progress he failed to offer anything beyond that. No vision, no real plans other than a ‘steady as we go’ approach that sought to only solidify his core support and bring in just enough middle income voters to secure a win. It was a strategy that would have failed under the best of circumstances and one that would not generate any strong interest during a campaign where the central theme was to unseat Harper himself. The Liberal Party under the telegenic Justin Trudeau did sense the need for change and borrowed heavily from the Obama playbook by proposing exactly that, all outlined in an endless array of proposals intended to bring that real change to Canada. And yes, there was some audacity involved in proposing to abandon first-past-the-post elections, legalize marihuana, ramp up infrastructure spending, address climate change and rewrite a few conservative bills like C-51. There are two caveats to this of course, one being that Trudeau promised so much that it will be nearly impossible to deliver on all of it during his four-year mandate. Just imagine how his freshly minted caucus feels about abandoning first-past-the post. The other aspect is that Trudeau did not present a clearly defined vision; the change for change sake does not constitute a plan for the future as the Obama supporters have found out. It does deliver on a few specific items but fails to take on larger, generational issues like demographics and the challenges it poses for the family, healthcare and retirement or a redefined global map which in turn drives economic challenges and brings about new strategic relations. As one younger voter told me, “none of the candidates talked about technology” and that is a pretty serious indictment. The more ideological driven parties fared no better, although to be fair to the Greens and the NDP they are operating under both an electoral system and regional differences that make it quite hard for them to be really competitive across Canada. The NDP rather than by embracing the increasing skepticism on the left (and the right) of the sustainability of capitalism and austerity as we now know it, doubled-down on a tack to the center approach which made its leader Thomas Mulcair somewhat indistinguishable from Harper and Trudeau. Europe has an array of social-democrats that have fallen into the same trap and taken a brutal clobbering at the ballot box which is exactly what happened to Mulcair. The Green Party saw an opening in this electoral mess while capitalizing on the renewed interest in environmental issues and believed it had its best chance yet to capture more than one seat and start making a real difference. Not so. All three of the larger parties had started to embed green ideas into their platforms with the Liberals and NDP proposing a lot of what the Greens were offering in terms of support for families, small businesses and health. Trudeau’s initiative to invite Elizabeth May to join both him and some of his ministers to a climate summit in Paris will only strengthen his hand. No one can imagine them letting May take credit for any progress at the summit and if they do, it will be seen as a Liberal success, not a Green one. But let’s return to the election. Most staggeringly was the inability of all parties to address foreign policy in a time where a more isolationist America, a more assertive China and Russia, not to mention a devastating religious and generational conflict in the Middle East is creating a sea of instability last seen in the 1930s. So by way of example, the Conservative Party’s instinct to defend our partnerships in bombing ISIS was right, it totally failed to really address the fundamental issue in Syria which is that the root of the crisis (and mass murder resulting in endless streams of refugees) is its current leader, Assad, and not just ISIS. The fact that a supposedly smart and well-organized campaign kept droning on and on about ISIS while one simple look at Twitter could have told them that drowning refugees could more readily be attributed to Assad was one more piece of evidence of how superficial this campaign was. Not that the left had anything intelligent to say about this. Trudeau, May and Mulcair all trumped a resort to the past – how is that for visionary policies – where Canada would pull out of fighting missions and revert to peacekeeping, whatever that means in today’s world. Re-imagining a peaceful world with Maple Leaf carrying soldiers handing out blankets is reminiscent of the same nostalgia that sometimes envelops European elections where the stable and culturally uniform 1950s are presented as the ideal age of western civilization. The only problem is that the world has changed, a bit. Presenting a vision of the past in the end is not the most sound way to prepare for the future. And the future looks decidedly different. And again preparing a vision or a reasonable argument for a challenge by that very future helps a politician. The Conservatives sensed that the 'niqab’ was one such issue that would deliver them votes, by harking back to the past where the 'niqab' was not something that was part of daily Canadian life. And it would probably play to the Conservative fortunes in a province - Quebec - where there had been a deep debate about religious and cultural symbols (and let’s just park the discussion as to whether the ‘niqab’ is a religious or cultural expression). But team Harper completely misread the nature and context of the ‘niqab debate’ and one has to wonder what sort of campaign smarts were involved in unleashing this without any solid thinking onto Canadians. Don’t get me wrong, it is an issue worth debating and finding a solution to as the former Liberal leader Ignatieff alluded to or by assessing how the French have dealt with it with a number of years ago. The problem was that the Conservatives dropped it in the middle of a national campaign where it was (a) not an issue and (b) if it were one it was a regional, ie. Quebecois issue. And then it totally bungled the topic itself while harping (excuse the pun) on about citizenship ceremonies while not addressing that the issue – as the socially liberal French and Dutch have found out – is one of dealing with fundamentalist forms of religion present in increasingly secular societies that take personal liberties pretty seriously. None of that, alas, and what followed was a shameful and intellectually unhinged debate where no one got it right. Of course the Liberals, NDP and Greens jumped on Harper about being divisive, which may have helped them during the campaign but failed to address the opportunity it really created, namely talking about what a multi-cultural future for Canada could really look like. To be clear, this is not an easy undertaking and something which very few democracies have been able to articulate well, but it would be not too much to ask our politicians to not use the ‘niqab’ as a wedge issue but as a starting point to create a forward looking vision for Canada. By remaining stuck in past and ideological boxes all parties failed and it underlines the fear that an inward looking and rosy view of Canada in no way prepares the nation for the challenges that lay ahead in the 21st century. Now that the smoke has cleared and we are getting ready for Trudeau’s inauguration it is a good time to assess what happened during Canada’s longest election ever. A successful incumbent failed to make a credible bid for re-election while having all the tools at his disposal to do so. That is something for the Conservatives to ponder in the coming years. The ideologically driven opposition of social-democrats and greens failed to present a credible future vision and got entangled in a lethal mismatch of a ‘Canada past’ and electoral maneuvering. The NDP has a real shot at rethinking what the ‘left’ really represents in the 21st century by trying to cleverly address the dark side of capitalism. The Green Party should do the same, but only real electoral reform can save them from eventual obliteration as the ‘green message’ has now been co-opted by all the other parties. And that leaves us with the election’s winner who if you really think about it, did not win by articulating a vision for Canada, but who won by default. I did not vote for Trudeau, but I do admire some of his bolder proposals that will hopefully bring about things that can help unify Canadians in their purpose. The scope of his agenda is however most likely too ambitious to deliver in four years at which point in time we can only hope the parties can give Canadians a real peak into aspirations for the future. In that sense Trudeau is not an aspirational, but a transitional leader. Photo: rather than the ubiquitous party leader photo I grabbed one I took of the ferry departing Bowen Island last year. With the Canadian flag it sort of says that we are leaving something behind and going into uncharted waters. |

Archives

April 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed