|

Some lessons for life and political success: staying at it

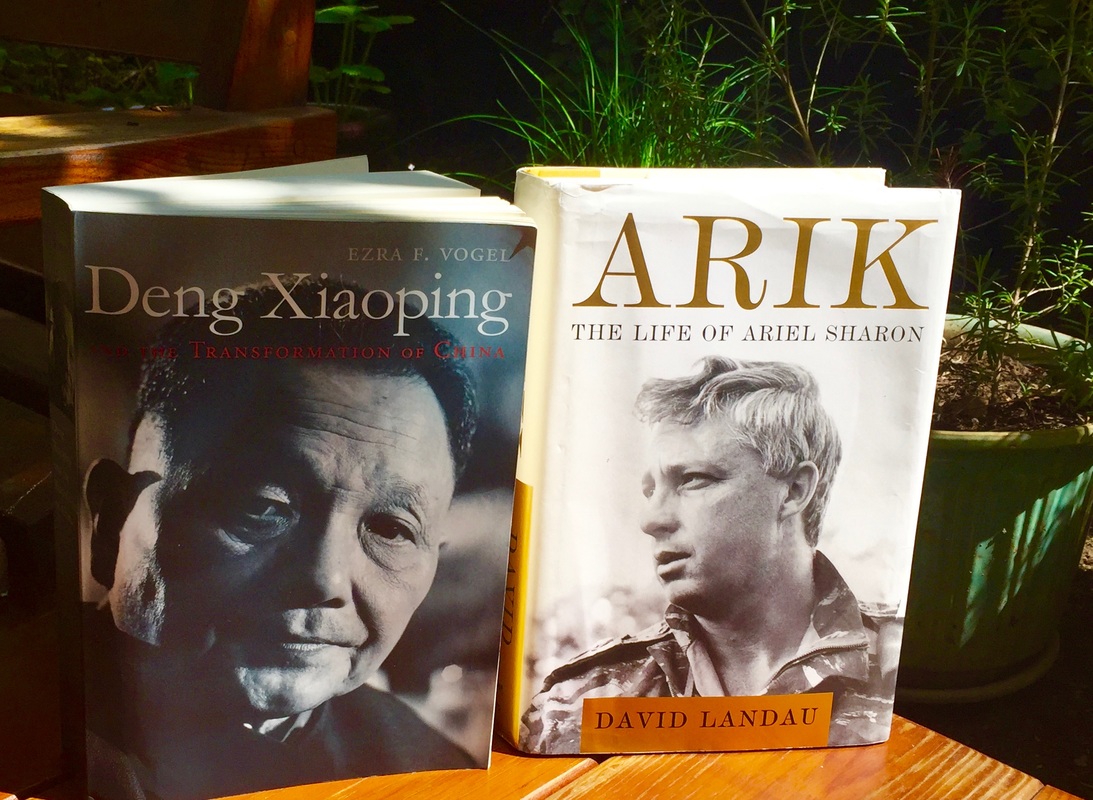

It is surprising to some extent to see how the world these days devours ‘self-help’ and or ‘career advisory’ books, all promising to deliver the right tools and techniques to bring us riches and happiness or some sort of combination thereof. It was a relief for me this summer to return to my old passion of reading political biographies and to realize that all the clues to happier lives and better careers can easily be found by studying the lives of some of history’s great and see how they navigated some of the deeper challenges that defined their lives and come out as winners. So this summer I dove into David Landau’s epic work on the life of Ariel Sharon and it was followed by the deeply researched and voluminous biography that Ezra Vogel put together on Deng Xiaoping. As a historical figure, Sharon tends to generate some negative reactions given the abrasive style he was known for, his presumed guilt in the Sabra and Shatila massacres and triggering the second intifada following his visit to the Temple Mount in 2001. Both of these claims by the way are clearly and helpfully dispelled by Landau’s book. Deng however usually can count on a far more sympathetic treatment as the man that transformed and modernized China. This of course is somewhat questionable as Deng most probably had been far more directly involved in unleashing lethal force, on his own subjects no less, during his career as one of Chairman Mao’s key enforcers and eventually as China’s paramount leader. During my years in Asia it was not unknown to hear business leaders praise the bloody crackdown in Tiananmen as one of the essential building blocks of a stable China that is open for business. Whatever the merit of that morally flawed argument, both Deng and Sharon built their careers in newly formed nations – Israel being established in 1948 and the People’s Republic of China only one year later, 1949 – that were under such formative pressures that the internal and external use of force were essential parts of the job. Although China and Israel came into being under vastly different circumstances and cannot be compared in terms of size and histories, the parallels between the careers of both men are striking. Both biographies clearly present that their entire lives were essentially in the service of their nation and that both consequently took a deep personal toll in the process. These were compounded by significant personal dramas. Landau’s description of the death of Sharon’s young son Gur is moving and heartbreaking, much the same can be said for the way Deng’s son Pufang was denied medical treatment during the Cultural Revolution a result of which he spent the rest of his life in a wheelchair, paralyzed from the waist down. It is a testament to the quality of the books that you can sense how the deep pain of these personal tragedies accompanied these two men for the rest of their political lives and how it motivated them. Yet the essence of both careers was that it took a lifetime to get to the top positions, Deng being a solid seventy-four when he could truly claim to be China’s paramount leader, Sharon was seventy-three on the day he was inaugurated as Israel’s prime-minister. Both books give a very detailed accounting for the reasons it took so long and how both men persisted against the many different forces that were aligned against them. The pragmatic fixer Deng had the nearly insurmountable task to carve out a space for plain reason and common sense progress in the toxic environment created by Mao’s continuous political struggles where dogma trumped everything else. Deng was purged from the leadership twice: in 1966 and within about a year of returning from the first one, in 1976. Both of these had career ending potential, yet Deng not only overcame both events, he emerged stronger and far more decisive. Sharon in turn had to navigate a different but equally explosive political environment in Israel – Landau’s book is a key primer to get a feel for the machinations of Israeli political power-play – but also his own character which at times created some roadblocks on avenues that had opened up for him. The benefit of the long road that both had to travel was of course the accumulation of deep experience and a huge personal network of politicians, administrators and military commanders complemented by an incredibly clear and growing sense of direction for each nation. This of course was compounded by the fact that by the time they reached the highest office there was little time left for them given their advanced age. For Deng it meant rejecting orthodox communism and embracing capitalism while maintaining one-party rule, for Sharon it was ditching the nationalist settler movement that propelled him to power and embrace disengagement from the Palestinian enemy. Once you come to the end of Sharon’s biography it is both harsh and painful to see how he in early 2006 succumbed to a hemorrhagic stroke that sent him into an eight-year coma from which he never woke up. The remaining question that even the masterful Landau can not answer is whether Sharon would, following the departure from Gaza in 2005, have continued his unilateral disengagement by withdrawing from the West Bank and setting the stage for more favorable conditions for Israeli-Palestinian peace than is the case now. What we do know is that had Sharon lived as long as Deng, he would no doubt have left an even deeper imprint on the Middle East. Deng retired from the political scene in 1992 having reached the tender age of eighty-eight and as opposed to Sharon, did live to see most of what he set out to do: a stable and steadily growing China. So what do these old men of state and their biographers have to tell us about our lives and careers? The same lessons that drove Deng and Sharon to ultimate success in their lives and careers. Hard work, focus, family and never ever giving up. Note: Deng Xiapong and the transformation of China by Ezra F. Vogel (2013) and Arik: The Life of Ariel Sharon by David Landau (2014). As a complement I would recommend reading The Cultural Revolution: A People's History, 1962-1976 by Frank Dikötter (2016) which gives a bit more depth and analysis of the horrors of the Cultural Revolution an area on which Vogel’s book was a bit light.

0 Comments

|

Archives

April 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed